Fascia is the hidden link that connects every move you make. It envelopes and intertwines with muscles, bones, organs, and nerves, forming a continuous web that provides support, protection, and organization to the body's various structures.

And this powerful web plays a key role in strength, power, mobility, and overall performance. In this article we’ll break down what exactly fascia really is and why, as a Free Athlete, you should focus on training it and keeping it healthy.

What is fascia?

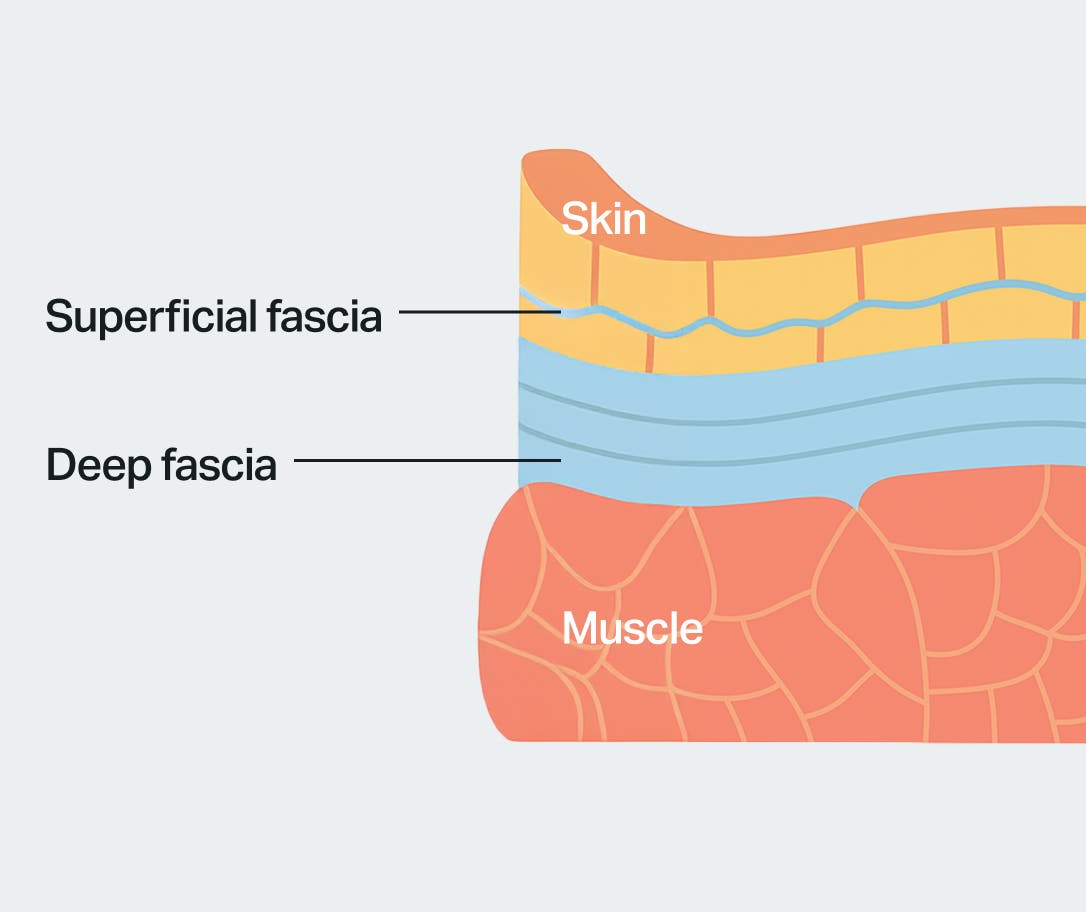

Fascia is broken down into three categories: superficial, deep, and visceral.

- Superficial fascia, located just beneath the skin, acts as a protective layer and plays a role in temperature regulation and energy storage.

- Deep fascia, found beneath the superficial layer, forms dense sheets or bands that encase muscles and groups of muscles, supporting them and facilitating smooth movement.

- Visceral fascia surrounds the body's internal organs, offering them protection and allowing for proper positioning and function.

This multi-layered system serves as an integrated framework that holds the body together, ensuring stability and coordination during movement.

But fascia does so much more than just providing structural support. Recent scientific research has shed light on the vital role fascia plays in several important bodily functions.

For example, fascia is now recognized as a key player in proprioception, the body's ability to sense its position and movements in space.1 Specialized sensory receptors embedded within the fascial tissue contribute to proprioceptive feedback, enabling precise coordination and control of movement.

Fascia is also involved in how the body senses and processes pain. Nociceptors, our pain-sensing nerve endings, found within the fascial matrix, allowing it to transmit pain signals in response to tissue damage or dysfunction.

This matters because when fascia becomes restricted or dysfunctional, it could contribute to chronic pain conditions, highlighting the importance of maintaining fascial health for pain management and rehabilitation.

In addition to movement and pain, fascia also helps regulate the body's immune system and keeps tissues balanced. Immune cells located in fascial layers continuously monitor the surroundings, identifying and reacting to possible dangers like infections or injuries.

Fascia acts as a pathway for lymphatic fluid, enabling immune cells to move around and remove waste from tissues efficiently.

Influence of fascia on body movement

In its optimal state, fascia facilitates smooth and coordinated movement throughout the body. It acts as a dynamic platform, allowing muscles to glide past one another with minimal friction.

Healthy fascia promotes the efficient transmission of forces, contributing to athletic performance and agility. However, fascial health can be compromised by injury, inflammation, or prolonged immobility.

Restrictions, adhesions, and scar tissue

When fascia becomes unhealthy, it can lead to a variety of issues that affect the body's overall function and well-being.

- Restricted movement: Unhealthy fascia may develop adhesions, scar tissue, or a feeling of tightness, which restricts the natural movement of muscles and joints.

- Musculoskeletal pain: Fascial restrictions can cause tension and compression on nerves, muscles, and other soft tissues, leading to localized or referred pain.2

- Poor posture: Tight or imbalanced fascia can play a role in biomechanical inefficiencies and may even influence posture negatively.

- Compensatory patterns: When fascial restrictions occur in one area of the body, adjacent muscles and tissues may compensate to maintain function.

- Impaired circulation and lymphatic drainage: Fascial restrictions can compress blood vessels and lymphatic channels, impairing circulation and lymphatic drainage.

- Nerve compression: Tight or adhered fascia may compress nearby nerves, leading to numbness, tingling, or shooting pain along the affected nerve pathway.

- Digestive and respiratory dysfunction: Fascial restrictions in the abdominal or thoracic regions can affect the function of organs such as the intestines, lungs, or diaphragm.

Imbalances within the myofascial system can have far-reaching consequences. A restriction or dysfunction in one area of the body can trigger compensatory patterns elsewhere, leading to a cascade of biomechanical alterations.

This domino effect often manifests itself as any of the above and can be brought on by common daily routines, such as prolonged sitting.

Effects of prolonged sitting on fascia and remedial actions

The modern sedentary lifestyle has profound implications for fascial health, along with just about every other health category.

Prolonged sitting promotes stiffness and adhesion formation, particularly in areas subjected to prolonged pressure, such as the lower back and hips.

Sitting for extended periods causes skeletal muscles to adaptively shorten and fascia to become less pliable, leading to increased muscle tension and discomfort.3

Poor posture and repetitive movements associated with sitting can exacerbate fascial restrictions and contribute to musculoskeletal imbalances.

Steps to maintain fascial health

Preserving fascial health requires a multifaceted approach encompassing various lifestyle modifications and therapeutic interventions:

- Regular movement: Engage in regular physical activity to promote circulation and prevent fascial stiffness. Incorporate a variety of activities such as walking, running, swimming, or yoga to target different muscle groups and movement patterns.

- Hydration: Adequate hydration is essential for maintaining fascial elasticity and lubrication. Drink plenty of water throughout the day to support optimal tissue hydration and facilitate nutrient delivery to cells.

- Stretching and foam rolling: Incorporate stretching and foam rolling exercises to release tension and restore fascial mobility. Focus on areas prone to tightness or restriction, such as the hips, shoulders, and lower back.

Perform dynamic stretches and self-myofascial release (SMR) techniques to improve tissue flexibility and alleviate discomfort.4 - Massage therapy: Seek professional massage or physical therapy to address specific fascial restrictions and adhesions. Massage techniques such as myofascial release, deep tissue massage, and trigger point therapy can help break up scar tissue, release adhesions, improve tissue mobility and even relieve pain.

- Mind-body practices: Practices such as yoga and tai chi can enhance body awareness and promote fascial resilience. These mind-body exercises emphasize movement quality, breath awareness, and mindful relaxation, which can help reduce stress and tension in the fascial system.

Lets recap

Fascia is a fundamental yet underappreciated component of the human body. It plays a crucial role in facilitating movement and maintaining structural integrity.

Understanding the influence of fascia on bodily function is crucial for preventing injuries, managing muscle pain, and optimizing physical performance. By adopting proactive measures to preserve fascial health, you can unlock your body's full potential and enhance overall well-being.

Sources

[1] Schleip, R., Klingler, W., & Lehmann-Horn, F. (2005). Active fascial contractility: Fascia may be able to contract in a smooth muscle-like manner and thereby influence musculoskeletal dynamics. Medical Hypotheses, 65(2), 273–277. [DOI: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.01.026]

[2] Stecco, C., Stern, R., Porzionato, A., Macchi, V., Masiero, S., & Stecco, A. (2011). Hyaluronan within fascia in the etiology of myofascial pain. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy, 33(10), 891–896. [DOI: 10.1007/s00276-011-0833-7]

[3] Langevin, H. M., Fox, J. R., Koptiuch, C., Badger, G. J., Greenan-Naumann, A. C., Bouffard, N. A., & Konofagou, E. E. (2011). Reduced thoracolumbar fascia shear strain in human chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 12(1), 203. [DOI: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-203]

[4] Standring, S. (Ed.). (2016). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (41st ed.). Elsevier.